Adrián Villar Rojas – The Work of the Ocean

Datum

Adrián Villar Rojas

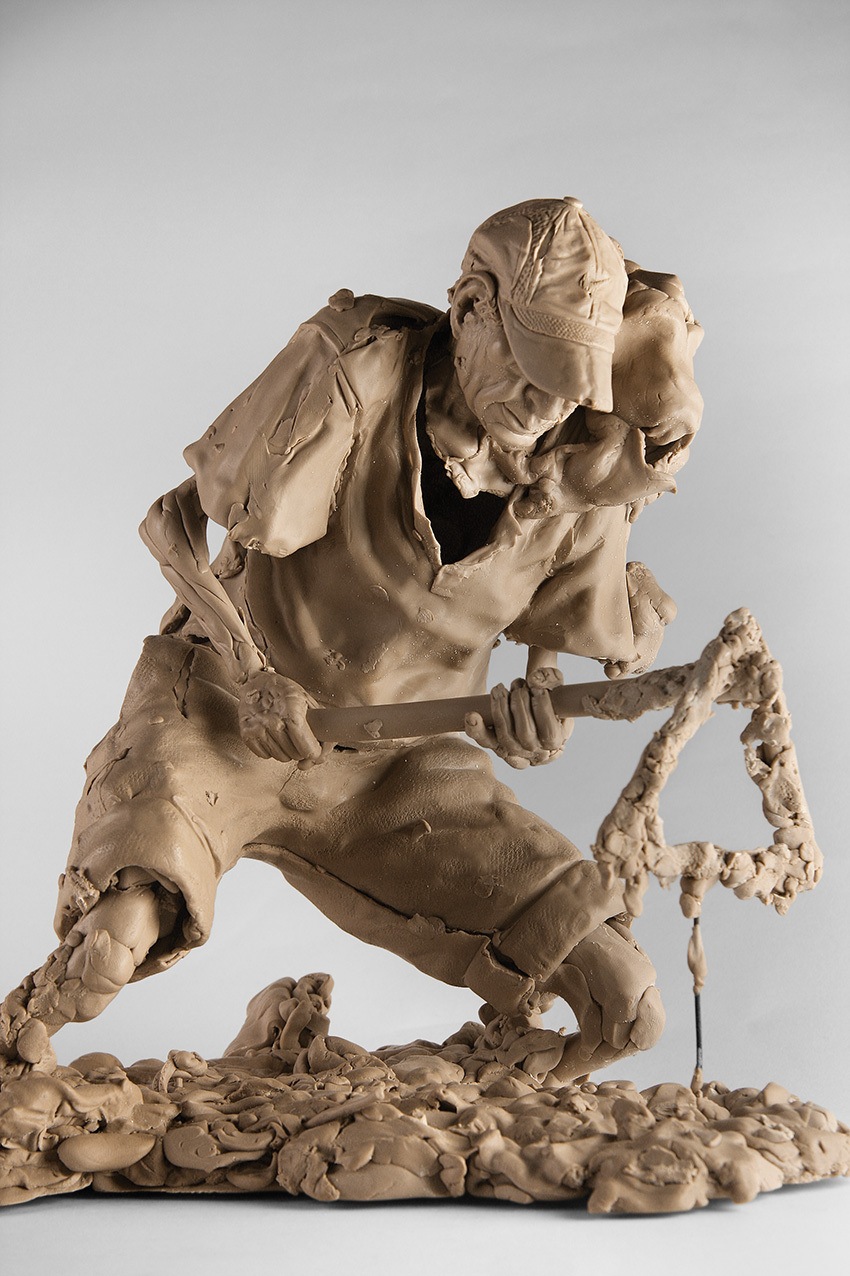

‘…clay enabled me to build fossils: I could fossilize whatever I wanted, and thus I could work with time. I could fictionalize the passing of time by representing its effects on matter.’ The discovery of clay was an epiphany for the artist; as he says, ‘I could build my own ruins’. But clay has a deeper significance beyond this, as an elemental life force: ‘I dare to say that clay itself has pretty much been the ideological, narrative and aesthetic engine that engendered the universe.’

The epoxy putty replicas in Brussels are, then, twice removed from works that were themselves the signs of an elsewhere, of another time and another space. In Kassel, the large works told of geological time, of the epoch of human existence and its eventual disappearance. Grand monuments to entropy and extinction, the interplanetary, the hypothetical and the multiversal. Villar Rojas has spoken to me, in geophysical terms, of wind, rain and sun as ‘sculptural forces’, but also of the otherworldly and the fantastical, of science fiction, and romantic heroes like Kurt Cobain. Here, at ‘De 11 Lijnen’, we seem instead to be brought back, with a dull thud, to the present tense of everyday life in the affluent North in 2013 – to Belgium perhaps. Curtains and cushions. The material shift from clay to putty means that the miniature works are not susceptible to the same processes of decay that were so important to the Kassel works, as they are to all of Villar Rojas’s clay sculptures. Without this degradation, they are unable to function as the sign of decay, and the sign of time. The durability of their material renders them ‘conceptually feeble imitations’ of the originals, as the artist has put it. Villar Rojas speaks of ‘impoverishment’. Indeed, they are a paradox, doubly ‘deprived of their condition as ruins’. Among the miniatures, some are derived from the human figure sculptures shown at dOCUMENTA(13), and yet they are less than human, and rather closer to the throwaway commodities and junk that fills ourhouses, and that tends to gather and accumulate from nowhere like a rumour.

There is a third space, a third rumour: a brick-farm in Rosario, Argentina, Villar Rojas’s home city. Here, a sculptor from La Plata, near Buenos Aires, has produced the epoxy works under the supervision of Villar Rojas, having previously assisted the artist on his project for Kassel. A number of the miniatures have their origins in the brick-farm – a family of horses, some dogs, a child with a knife – and so the Belgian installation functions as a tapestry of quotations drawn from two worlds. A brother and a sister are at the centre of this rumour; they have travelled from Argentina to Belgium carrying only the small sculptures and two video cameras. On arrival at ‘De 11 Lijnen’, they have set about fabricating the domestic space within the expanded gallery, situating the sculptures, and filming each other in the process for a period of more than twenty days. Rosario itself becomes what Villar Rojas calls a ‘ghost’; it is present in its absence from Oudenburg in the shape of an exquisite publication that functions as a record of the brick- farm project. Villar Rojas, it is true, has an urge to document. He constantly records by way of photographs and videos. This impulse relates to his desire to create monuments, which he has explained to me in terms of his ‘strong feeling of having to fix things, to fix moments as a way to save them from a sort of nothingness, which inexorably dooms everything and everyone’. Documentation also arises as a key aspect of his working practice because process and becoming are his enduring subjects.

As he has told me: ‘I feel that something beneath and beyond the sculptures is going to happen, something in the process itself … it is not about the final works, but about what happens in-between.’ The Work of the Ocean is expansive. It could perhaps be considered the afterlife of Villar Rojas’s Kassel project, which means that it has crossed the ocean twice, from Europe to Argentina, and back to Europe again. What has happened in-between here is an epic journey of retrieval and reconstruction. But like a rumour, it is founded in disappearance. There is an absence at its centre, which is revealed to be time itself. Time dwindles with the loss of its material trace. There is only the ghostly present, ever facing its decay.

BIOGRAPHIES